IT HAD TO BE IMPRESSIVE

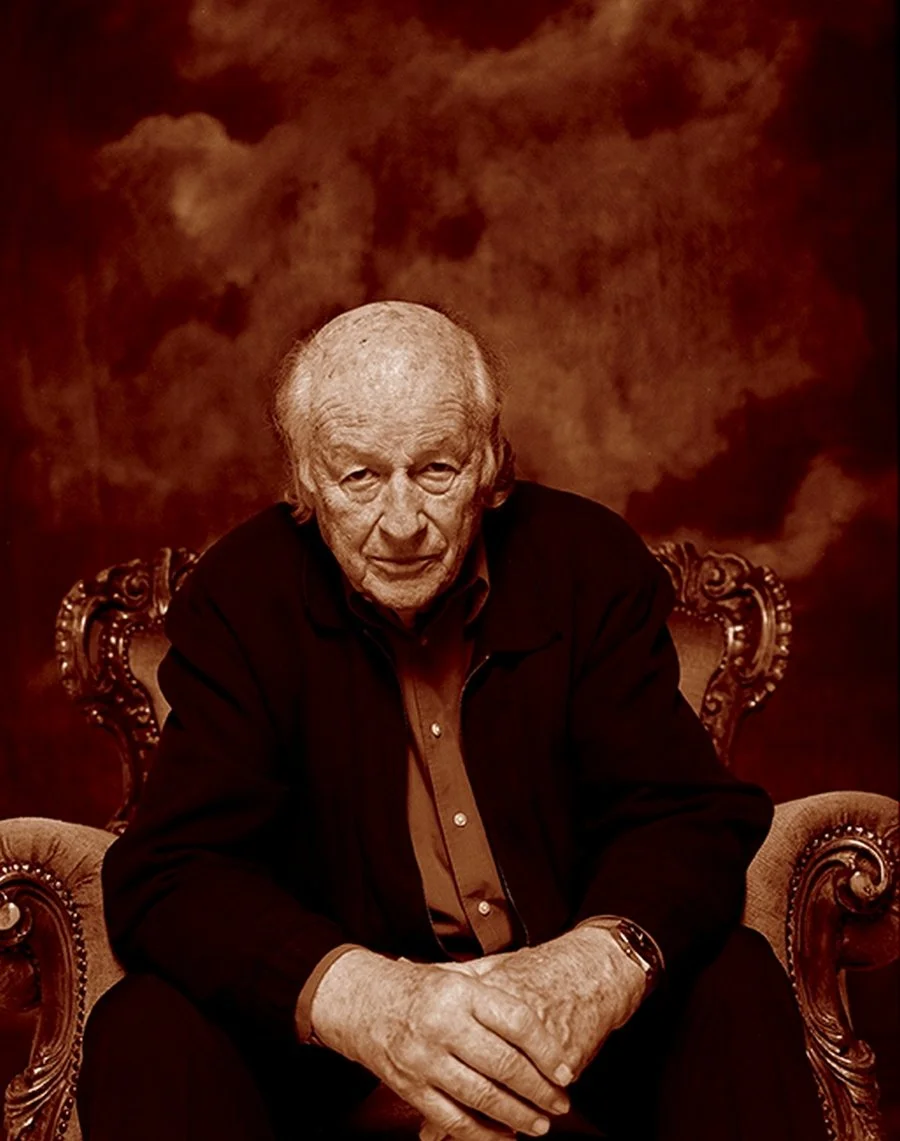

RAY HARRYHAUSEN

At the age of 85 special effects legend Ray Harryhausen (June 29, 1920 – May 7, 2013) came to Amsterdam to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Amsterdam Fantastic Film Festival. This was in June, 2005, about a year after he had published his book An Animated Life. Phil van Tongeren and Roel Haanen had the pleasure to sit down with him and get the master's response on a couple of movie clips they brought along. Some of which he had worked his magic on, some of other films. One thing they were curious about, was how Harryhausen, who retired after CLASH OF THE TITANS in 1981, felt about the computer generated imagery that had taken over practically all special effects in Hollywood.

Movie clip: 20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH (Nathan Juran, 1957). Stop-motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. The scene: the Ymir, a Venusian monster, crawls out of its egg and rubs its eyes.

20 Million Miles to Earth

Harryhausen: Oh, this is 20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH.

We selected this scene because it’s so cute. Did you that on purpose, have the Ymir rub its eyes, to win the audience over for the monster?

Absolutely. I always tried to give them character. That’s the first law of animating, otherwise you end up with something that’s moving for the sake of moving. So, I always give them character. I learned that from doing the fairy tales many years ago as well as from KING KONG. Because that film really set me off on my career. I saw it when I was thirteen and haven’t been the same since. That shows you how influential a film can be.

When you design a creature, how does its personality evolve?

It’s spontaneous I suppose. One pose leads to another pose and so on. So, you’re constantly thinking about what it’s going to do in the periphery of the story. Now, Ymir went through so many changes, as you can see in the book [An Animated Life]. At one time he was really stout, he had two eyes and then one eye, two horns sticking out, and so forth. It’s a sort of lizard and it’s hard to get sympathy from the audience for that. So ultimately I wanted to give it a semi-human form. And then I could add all these nuances because I used one flexible figure. When I worked with George Pal we had 25 separate figures to take one step. They were all cut out of wood and they had to be heavily stylized. but Willis O’Brien who did KING KONG and THE LOST WORLD devised this single figure, which was whole jointed. You could move it when the shutters closed and take a picture. It’s a long process and it’s not everybody’s cup of tea… It’s how I lost my hair. [Laughs]

You always worked by yourself, right?

Yes, I prefer to work alone. It requires a lot of concentration. If you have people around you forget what you’re doing.

And you always operated in total artistic freedom?

Yes, nobody tells me what to do! [Laughs]

Movie clip: SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW (Kerry Conran, 2004). The scene: gigantic robots attack New York City.

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

Hmmm. What is this? Is it a GODZILLA movie?

No, it’s SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW.

Oh, I never saw it.

We chose this because it uses new technology to make the film look old fashioned, like METROPOLIS or an old Flash Gordon serial.

It’s very effective, visually. But see, there’s one problem: CGI is so overused. When I started out with THE BEAST FROM 20.000 FATHOMS, the unusual visual image was impressive because you seldom saw them on the screen. Now, in a 30 second commercial you see the most amazing things. So, nobody’s amazed anymore. That’s the trouble with CGI: it kills its own spectacular images by overuse. Each movie tries to top the other and the next producer says he wants to make it even bigger and pretty soon it’s just a big jumble of special effects. It has no adherence to the story anymore. We tried to make our animated characters a part of the story instead of an insert of special effects.

When I saw King Kong appear on the screen for the first time, I knew it wasn’t real, because it couldn’t be real. But it looked real! I just couldn’t figure out how it was done! And now, magazines come out telling you how the special effects were done even before the film is released. If a magician tells you how he’s going to pull a rabbit out of his hat, you’re no longer interested in the trick, are you?

In this scene New York City is almost destroyed. You destroyed some cities yourself in your films.

Yes, but I got tired of it. When Godzilla got in on the action and destroyed Tokyo, I didn’t know where to go from there. I had destroyed Rome, the Golden Gate Bridge, Coney Island…

Your movie THE BEAST FROM 20.000 FATHOMS was similar to GODZILLA but it almost never gets credited for being first.

Never. We did it first and GODZILLA was practically a copy. It was the same story. After GODZILLA I started looking for a new avenue for the use of stop motion and I came across the Sinbad stories. If you have James Bond fighting a skeleton it would be comical, but if it’s a character from legend you’ll believe it. I think that fight turned out rather well. It was the highlight of the picture. And when it played in England, they cut the whole skeleton fight out of the picture!

Why was that?

They thought it would frighten children.

But wasn’t that the whole idea?

Of course! [Laughs]

Movie clip: THE MIGHTY PEKING MAN (Meng Hwa-Ho, 1977). The scene: Giant ape ‘Peking Man’ must watch helplessly from behind bars how his girlfriend is sexually assaulted by a carnival boss. Peking Man becomes angry and breaks loose.

The Mighty Peking Man

What’s that heavy breathing? It sounds like raw passion! [Laughs] What is this?

This is called THE MIGHTY PEKING MAN. It was made to cash in on the Dino De Laurentiis’ remake of KING KONG.

Looks terrible. That’s a man in a suit! Pathetic!

What did you think of De Laurentiis’ remake? That also uses a man in a suit.

I have nothing to say.

But you have seen it.

Unfortunately.

You really have nothing to say about it?

Well, I always tell people that if I had seen the De Laurentiis version in 1933 I would have become a plumber. But I think if I had seen this PEKING MAN I would have become a garbage man. [Laughs]

You were attached to a KING KONG remake in the sixties.

Yes, it would have been produced by Hammer, but we never got further than talks, because the copyrights proved too complicated. If I had done it I would have stayed very close to the original, because I don’t see how you could improve on it. There’s no Max Steiner to do the music.

What do you expect of the Peter Jackson remake?

Well, it will be his own interpretation, but at least Peter Jackson has taste. And he loves the original as much as I do, so I think it will be good. I saw some of the sketches and they looked very good. At first he was going to use stop motion, but then he decided against it. He will use CGI.

You know so much about the craft, does the original KING KONG still…

Yes! I still enjoy it. The first time, when I was thirteen, my jaw was hanging on my navel. That is not the case anymore, but I still like it. I have seen it over 200 times. Some people would call that eccentric.

Movie clip: WILLOW (Ron Howard, 1988). The scene: Willow tries magic to turn sorceress Fin Raziel back into human form. She morphs into a goat, a peacock, a turtle, a tiger, a woman, et cetera.

Willow

That’s called morphing.

Yes, it’s the movie WILLOW.

Oh, I never saw it.

This movie is credited as the dawn of digital effects. But if you look at it now, it looks pretty bad.

I don’t think it looks bad, but it’s just so illogical. In our films, when dealing with the fantastic, there always had to be a thread of logic throughout. Otherwise you lose your audience. The average person doesn’t have that wild imagination. For example: in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD I felt it was very important to have the magician be limited in his powers. I argued for that every time we discussed the story. Otherwise in the first reel he can go ZAP! and kill the hero. So every time the magician used black magic he would age a bit. That theme went through the whole picture. Limitation is what gives it a feeling of possibility. But something like this here, with the endless transformations, isn’t limited.

But I don’t understand why that should be a problem in this particular scene.

It’s too much transformations. What do you think about it?

I think it just looks bad.

No, it doesn’t look bad. It looks impressive! It’s just that the average person would have a hard time imagining all these transformations.

I can imagine a tiger turning into a woman.

What, you deal in the occult or something?

Clip: THE VALLEY OF GWANGI (Jim O’Connolly, 1969). The scene: cowboys are trying to catch Gwangi with their lasso’s.

The Valley of Gwangi

You see here, I like to have my dinosaurs with their tails to the ground. Today the concept is to keep the tails up in the air. Makes them look constipated, I think.

I just wish they didn’t make the dinosaurs so blue on the prints. It was a grey-blue originally and somehow went they printed it up the blue dominated. Makes it look like the animal is painted on afterwards. On some laserdiscs it looks much better, more grey.

This movie came out in 1969, just when Hollywood started to change.

Yes. This film should have been released ten years earlier. Willis O’Brien started it in 1942. He planned it, but never filmed it. The war came along and they canceled it at RKO. I got the script years later and thought: cowboys and dinosaurs! But unfortunately we came in at the end of the cycle. Nobody was interested in cowboys anymore. And the critics were horrible, just diabolical! No matter what you do, or how good you do it – I’ve discovered this in my 85 years on this planet – somebody will criticize it. They will even criticize the good lord Jesus Christ. Not to compare myself with him, but… they will criticize you. Everybody doesn’t see things exactly the way you may see them.

What did that do to you, the failure of this movie?

Well, it was disheartening. It took us two years to make it and we put a lot of work in it. Now people think it’s one of our better pictures, but at the time the general public wasn’t interested. Gwangi… the name sounds like Godzilla, like a foreign monster movie.

Wasn’t it called THE VALLEY WHERE TIME STOOD STILL originally?

Yes, for some reason they wanted to call it THE VALLEY OF GWANGI. But you needed a publicity campaign just to explain what Gwangi means! It’s an Indian word for giant lizard. But nobody knew that, so Warner Brothers just dumped it on the market.

Afterwards, did you take your career in another direction?

Yes, that’s why we went back to the Sinbad stories.

You have a great love of dinosaurs…

Oh yes!

Were you excited when you saw JURASSIC PARK?

Yes, they were very well done. But it’s a different kind of picture. You see, stop-motion adds a nightmare quality to the film. You know it’s not real. If you make fantasy too real, then it brings it down to the mundane.

Was JURASSIC PARK too real for you?

Some of it, yes. But it was very well done. Obviously it was a great success.

Did you ever talk to Spielberg about the dinosaurs being too realistic for your taste?

No, I’ve met Spielberg, but I never talked to him about it. I admire him a great deal. Him and George Lucas. They’ve done some marvelous things.

Movie clip: HELLBOY (Guillermo del Toro, 2004). The scene: Hellboy fights a giant monster with tentacles.

Hellboy

Look, somebody cut his horns of. Is he supposed to be the Devil?

Yes, he’s a devil, but he’s the good guy.

How can he be the good guy and also be a devil?

He was a small boy when he came from hell, and he’s ashamed of being a devil. So he cut his horns off. The movie’s called HELLBOY.

Oh, I know the director.

That’s why we chose this clip.

Did it make any money?

It wasn’t a huge success.

It’s got some interesting special effects. Look! That’s almost a Medusa.

We chose this movie because we read that Guillermo del Toro asked for your advice on the picture and that you turned him down because you thought the script was too violent.

Well, we discussed it. He interviewed me one time in America and he wanted me to get involved but it was a little too violent for my taste, yes. Look, everybody has a different approach. We had violence in our films too, but not like this.

Now, see? Why did that explosion occur?

Because Hellboy had a belt with a bomb on it.

Why didn’t he get blown up then?

Because… uhm… he’s indestructible?

No, because otherwise you wouldn’t have a film!

Movie clip: THE LORD OF THE RINGS: THE TWO TOWERS (Peter Jackson, 2002). The scene: Gollum fights Frodo for the ring.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers

What’s the little character’s name? Gollum? It’s very clever and works beautifully. You’d never know that was CGI.

But isn’t it too real for your taste?

No, it’s great. Magnificent. You couldn’t do that scene the same way with stop motion. This is incredible. They’ve got a great set up there in New Zealand.

Movie clip: MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Ron Underwood, 1998). The scene: giant gorilla Mighty Joe Young is causing havoc at a cocktail party. Harryhausen has a small cameo.

Mighty Joe Young

Ah, MIGHTY JOE. The remake. I have a small appearance in this. If you blink your eyes you’ll miss me. They cut a lot of our stuff. Terry Moore and I were there for ten days. We shot a lot. We were even running on our hands and knees the last night, but they didn’t use it. I still get residual checks. I even had to join the Screen Actors Guild! [laughs].

Did you like the film?

It’s a different approach. The original Mighty Joe was sort of a send up of theatricality. This one was about animal conservation, but for a film with such a serious subject I thought the gorilla was too big. It’s a good film and I enjoyed it, but it’s not something I would want to see again.

Are you often asked to do cameo’s?

Yes, I did several for John Landis. I was in BEVERLY HILLS COP 3 and SPIES LIKE US.

Movie clip: THE GIANT SPIDER INVASION (Bill Rebane, 1975). The scene: the giant spider attacks a small town.

The Giant Spider Invasion

Hmmm. I have nothing to say about this.

If you see a film like this on TV, what do you think?

Nothing, I just turn it off.

You don’t keep watching just to see what they did with the special effects?

No, not anymore. I’m not sixteen anymore. Unfortunately when you’re around this long you get bored with the same thing pretty easily. You won’t understand that until you get much older [laughs].

Was there ever a time where you would get angry if you saw really bad special effects?

I always tried not to. I don’t want my blood pressure to rise.

And if you see a film directed by Bert I. Gordon?

Oh, please! We won’t discuss those.

But did they feel like an insult to your craft?

Listen, all you can do is rationalize and say: everybody has a different approach.

Movie clip: FIRST MEN IN THE MOON (Nathan Juran, 1964). Stop-motion effects by Harryhausen. The scene: Professor Cavor makes contact with the moon men, the so called Selenites, which were created by Harryhausen.

First Men in the Moon

Ah, FIRST MEN IN THE MOON, our Wells movie.

It’s the first time you worked in Panavision. It led to some problems?

I used the rear projection system in most of my shots. When I tried to project a long, thin image it fluctuated in the middle. It probably could have been overcome, but we didn’t have the time or the money to make experiments. So I had to redesign the whole picture with traveling mattes.

In your book the whole process of Dynamation is explained in great detail, but for someone like me, who doesn’t understand anything technical, it’s still hard to figure out how the magic occurs.

You’re not supposed to know too much! [Laughs] I guess you have to have some knowledge of the technical side to understand it all. It took me years to write the book, because I used to keep it quiet. I felt I was giving secrets away if I explained my process. When I saw KING KONG I didn’t know how it was made, and that was half the charm. When I did EARTH VS THE FLYING SAUCERS I tried to make the saucers look big, so I had to bring them close to the camera. And there were three wires holding them up. You could see the wires because you were so close, so I had to paint the wires the same color as the background in each frame of film! The audience couldn’t understand how I did it.

The Selenites weren’t all animated by you. Some were children in costumes. Does that bother you?

Yes, it bothers me. But we had to do it this way, because if I had animated them all I still wouldn’t be finished today.

If you had made the film today, you would have been able to just digitally copy the Selenites over and over. Aren’t you ever a bit jealous of the possibilities film makers now have?

What good would that do me? When I designed THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD I wanted to make it as lavish as Alexander Korda’s THIEF OF BAGDAD. But nobody in Hollywood wanted to put up the money, so I had to go the other direction and make it very cheap. You have to compromise when you’re working on a budget. I tried to compromise in such ways that you wouldn’t notice it. It’s not always what I would like it to be, but that was the only way we could do it at the time. People don’t realize that when they start criticizing. When you’re making a low budget picture you have to get a visual image that’s impressive for very little money. Now with CGI it’s a different world.

But if you watch your films now, it’s almost unbelievable that they were low budget and that all the effects were created by one man.

Yes, but it’s true. The only time I had assistants was on my last picture CLASH OF THE TITANS. That was because we got behind on schedule. When you’re making double exposures and the sprocket holes aren’t accurate, you get a movement and you can see where the line is where the two images are joined together. And we lost a month trying to prove it wasn’t my equipment that was causing the problem, it was bloody Eastman Kodak! They didn’t punch the sprocket holes accurately, so when you ran them through the camera a second time, it wouldn’t quite match. ILM had the same problem, because they had sometimes six or seven exposures. They ended up punching the films themselves. They would get the blank film and punch their own sprocket holes. You know what Eastman Kodak said? Well, you don’t notice it when you’re making a regular film! Which is probably true. These problems had to be solved and I had to solve them myself, because I couldn’t ask anybody.

You worked so hard and so long on one film. When you finally saw it on the big screen, did it bring you joy?

Sometimes, yes. But sometimes I would notice where I had to compromise. That goes through your mind.

So how much of what you imagined is actually on screen? Is it like sixty or seventy percent?

Sometimes more. Sometimes it all comes out. But I don’t resent having to make low budget pictures and compromising, because it taught me how to put a visual image on the screen for very little money. That was the whole point of it. It had to be impressive. When KING KONG and THE LOST WORLD came out people thought the animals were real. Now you can see that they are not. But that’s also because we’re inundated with film nowadays. When I was growing up you went to the movies on Saturday to watch the new picture. Now you can choose between six or seven different screens. When you’re at home there are movies, when you’re in a bar there are movies. They’re everywhere.

I’ll never forget when I went to see a film called QUO VADIS. We went to see it down in Los Angeles at the Orpheum when it first opened. We sat next to a little old lady and her husband. We didn’t know them. Here you had the fall of Rome, you had flames going up, thousands of extra’s running across the screen. Very good acting, great direction. When the lights went up this little woman nudged at her husband and said: You know, honey, that was a nice little picture. You knock yourself out trying to make something important and a lot of people just don’t see it that way.

Ray Harryhausen, photographed by Jan Willem Steenmeijer

Related talks

This interview first appeared in a shorter version in the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws. Above is the full version of this talk, edited only for clarity.

Special thanks to Jan Willem Steenmijer for letting us use use wonderful photograph. Be sure to visit his website.