THINGS THAT COULD HAVE BEEN

TOBE HOOPER (2)

He made one of the best horror films of all time: THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE. Still, it also forever pigeonholed Tobe Hooper (Austin, 1943 – Los Angeles, 2017) as a horror director. Phil van Tongeren spoke to him at the Offscreen Festival in Brussels in March 2015, and tried to find out how Hooper himself viewed his career. “I would have liked to end up doing something like CHINATOWN.” This is part two of an interview double bill, as Phil’s colleague Barend de Voogd also had a talk with Hooper that same day.

The 4K of THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE played in Amsterdam last December, and it was a great success.

Was it? Oh, that is terrific. It took a lot of effort of preserving it and not destroy the original grittiness.

It was 16mm reversal, right?

Yeah, that was the cheapest way to go back then.

I used to make some short films that way myself, so I know how it can look. It tends to look a bit grey.

Yes, and in this case there was a lot of grain. That kind of MEDIUM COOL look was embraced by independent filmmakers back then.

And you wanted a documentary kind of look.

Yes. I shot a lot of documentaries before. To me the most important thing was the sound of truth, coming from the emotions.

Beginning with NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD in 1968 the horror genre underwent a drastic change. Were you aware of being part of that?

Yes, I was. I really was trying to make a film that I wanted to see and hadn’t seen before. My sensibilities had been finely attuned to what I wanted to see as an audience member. Even the great Hammer movies, on which I grew up and which I loved, they had gone away. There were a couple of movies that were different, like THE MEPHISTO WALTZ, but they were so Hollywood looking. A slick look and the musical score was predictable. They were always trying something that they just weren’t pulling off.

I made EGGSHELLS and it was kind of surreal. It didn’t get enough attention for me to get another job, so I had to do something that would get noticed. The things that got attention and that could be made for a low budget, were horror films. There were no rules, so long as it worked.

THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE came out of my sensibilities and my reactions to the times. I studied what made horror films work and I decided to place a story in the ambiance of death. An important factor was setting the audience up with kind of a creepy, gooey atmosphere. After that first scene at the graveyard the movie starts building veils of… ooginess. That’s a good word, although I don’t even know if it is a word.

The opening of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: veils of ooginess

I understand what you mean. When we look at genre film history from the outside, we tend to think that after NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD the flood gates opened and film makers started making movies like THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT and your TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE. Is that assessment correct?

Yes it is. I saw NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD when I was living in Austin, Texas. LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT was playing in San Antonio, but I hadn’t had a chance to see it. Had I seen it at the time, it would not have been good for me, because I would never have used a chainsaw. I didn’t know until later that there was a chainsaw in that movie.

But we should recognize that it also came from Vietnam, from the crimes in the street, from the way the media was changing. The times they were a-changing.

When I was conceiving the idea for THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE the local news in San Antonio was focusing their attention on horrible car accidents and showing bodies on the street. There was a popular song out, called Dead Skunk in the Middle of the Road. Now, that was the damndest thing. What does that even mean?

If THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE hadn’t become this phenomenon, could your career have taken a radically different turn? Was it even your ambition to become a horror filmmaker?

It could have taken a different turn, sure. When I started out I wanted to become a working director. I could have made comedies. Well, in a way I have made comedies. They are ironic comedies, but still.

Yes, I think it shines through in your films. I recently re-watched THE TOOLBOX MURDERS and apart from being gruesome, it’s also funny.

Yes, it isn’t played for comedy, but I like the laughter to come from a place of truth. I like it to be organic, for example from observing something that is peculiar.

Was film your passion when you were a kid?

Oh, yes. I was in a cinema from the day I can remember. Immediately after school I would go to the movies. I would see two or three movies a day, if possible. I would run from one theater to another. Or I would stay in the theater and watch the same movie again. This is how I learned.

When things became more sophisticated and better in my life, when I moved from Dallas to Austin, it was really great for me. When I got to the University of Texas, the audience there was very verbal. They would attack Hollywood films. They would boo and cheer and scream at the screen. I immediately adapted to that environment.

You said you wanted to become a working director. Did you have the feeling that you were being typecast as a horror director?

Yes, I fell into the hole. I was definitely typecast. I loved the European films of the time, the surreal films of Fellini. Everything I loved about film came from Europe at that time. Hollywood had very little to offer in terms of an alternative. Mostly they made silly things like PILLOW TALK. That was what was driving Hollywood at the time, so it sent me to the art movies.

There is definitely a European sensibility in [THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE]. I so much saw the change coming in movies, because I was in the middle of it. I was making a film that was artistic on one level, and at the same time very commercial. It was too close in the middle of that war dance, where the energy starts to circle. And I knew I was doing something special. Day after day, progressively, there was a certain point where I knew this was really going to be something. And that I was going to get another job after this one.

But I was also influenced by some American directors, of course. By Kubrick and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and the behavior of his characters. To me it was really funny. It also had a realism about it, at least something that I could perceive as realism. Also the films of John Frankenheimer, in particular SECONDS. That scene where Will Geer’s character is talking to Rock Hudson and he’s telling him that his life as a younger man did not work out. We, the audience, know that he’s sending him back to the cadaver file, to his death. But he’s talking to Hudson as if he’s a football coach who’s kicking someone off the team. I found that tremendously funny and poignant at the same time. These things were sneaking into my work.

After THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE you tried to stay in that spirit.

Well, it just became a part of me.

Tobe Hooper’s debut feature Eggshells

In the eighties there would always be lists of horror directors who were the most important to the genre. Your name was always up there, with Cronenberg and Carpenter and Craven. Did you feel part of a group? Were you a group? Did you meet and discuss each other’s work?

We finally did. We all got together and became very good friends. It’s really cool, because there isn’t any envy. It’s just a bunch of guys who understand. Not only do they understand the genre, they understand how the Hollywood establishment perceives us. And the way the industry has let us down.

In what way?

They keep us in a corner. That’s only in the United States. In Europe it’s different. Cinema is viewed differently here. In the States they are making films to sell toys. It really is all about money. Not that it shouldn’t be, but it’s all so over budgeted now. It’s all about keeping large blocks of money flowing. It’s like Ned Beatty’s speech in NETWORK about the earth being a college of corporations. It has little to do with the conception of art. Hopefully art can find its place in that.

But the past has shown us that it is possible to make interesting and good commercial films with big budgets and big stars.

Yes, it is possible. Right now the studios, more so than I have ever seen, are going through the process of wanting to collaborate on a vision. It’s too many people giving their input. They depersonalize the movies. And as a result they try to second-guess the audience. An ugliness is springing up in the genre branch of cinema, in all branches of cinema. These executives are so afraid that someone won’t understand something, that films have taken a turn in explaining themselves, leaving the audience nothing to do but to sit there and observe. Whereas in gaming you’re interacting. At the movies you should also be engaging, emotionally and intellectually, and not tell you what it is. You should say: Far out! I wonder what the hell that is? And after the movie is over, you are still putting pieces together. That would cause you to go back and see the film again. That kind of interaction is being sucked out of movies, and that is the result of too many damn cooks in the kitchen.

Talking about making movies on a bigger scale, an interesting period in your career was between 1982 and 1986, when you first did POLTERGEIST with Spielberg and after that three films for Golan-Globus. You came from independent filmmaking. How was that experience?

Oh, I was where I always wanted to be. And I had no problems with the transition. There were differences, like a lot more people on the set. But I really didn’t analyze the situation. I knew I had to stay on budget, because otherwise you’d get a terrible reputation. But in my world, that was the way it was supposed to be done.

Tobe Hooper with Steven Spielberg on the set of Poltergeist

Do you ever think that going to Hollywood to do POLTERGEIST was the wrong way to go?

It could very well have been the wrong thing. It’s something I think about a lot these days. What would have happened had I stayed in Austin at the time? But you now, there just wasn’t anything there. My dear friend Richard Linklater has stayed in Austin, but now, finally, there’s something of a movie industry. Background support, crews, even a studio. But at the time my chances of getting my next job were way better in LA than if I had stayed in Austin and tried to find the money for my next film.

How was it to work with Golan-Globus?

Oh, it was great. Really great. They told me to do what I wanted and shoot for as long as I wanted to shoot. I moved to London. It took a long time to set up LIFEFORCE. At one point, everything was being shot there: RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, STAR WARS and so on. You couldn’t find a sound stage. So I went to Rome, to Cinecittà, but the vibes weren’t quite right. I could do a British picture there if I really had to. Then I went to Madrid to check out the old Samuel Bronston stages, but the wooden floors were so rotten that we would have had to replace them. Then Yoram and Menahem bought EMI Elstree, so I had room to shoot.

That wasn’t where you shot INVADERS FROM MARS, right?

No, that was back in LA. That set was so huge that we used the warehouse that Howard Hughes built for the Spruce Goose. It was the largest set since Griffith’s INTOLERANCE, with the almost Egyptian façade, with the elephants and so on.

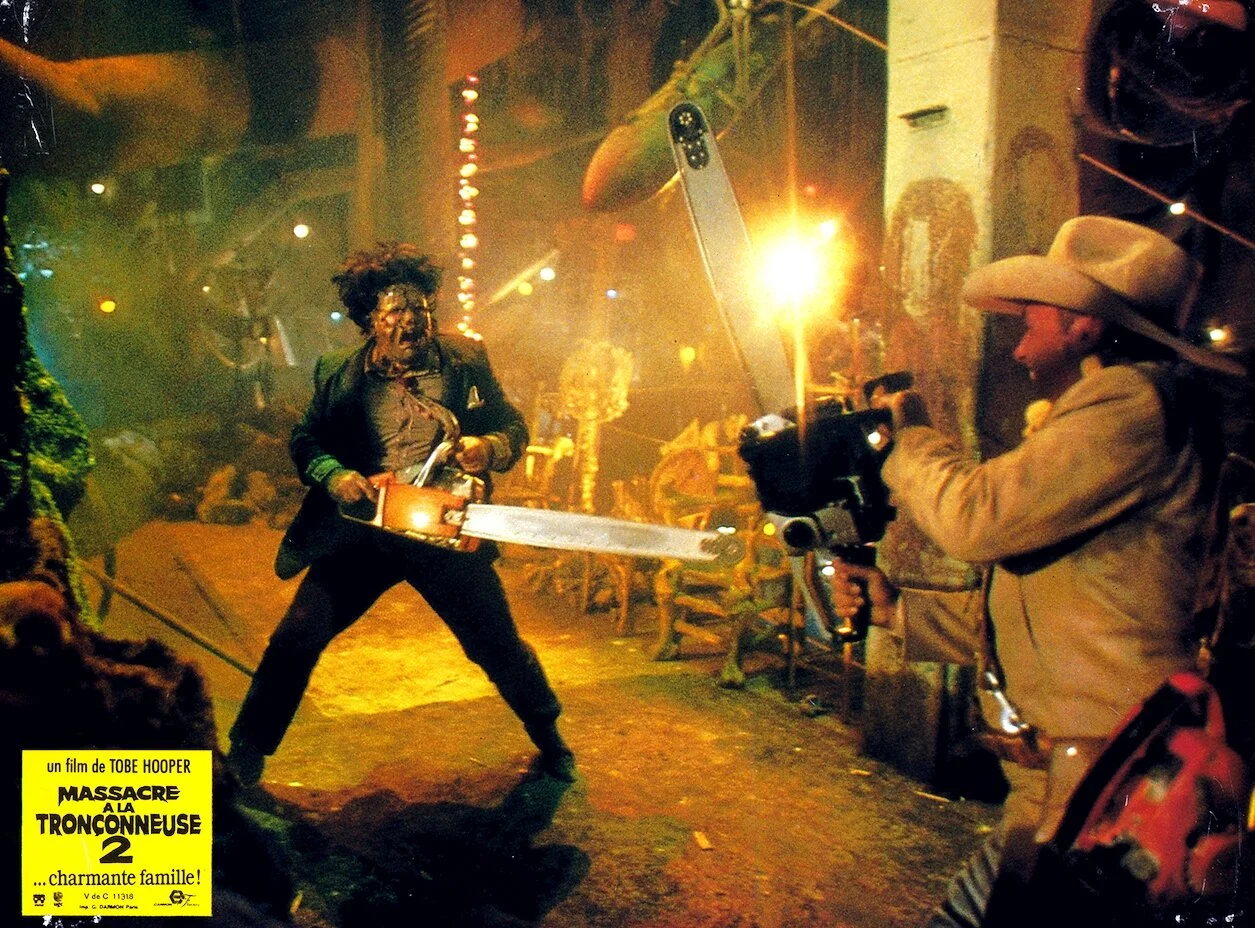

What inspired you to make THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE 2 so contemporary?

Well, we were living in a new time. There was Reaganomics, affluence, Ferris Bueller. And since very few people saw the ironic humor in the original TEXAS CHAIN SAW, I decided, rightfully or wrongfully, to make it a comedy, a film of its time.

So finally, you did a comedy.

Yeah! It was a comedy that couldn’t get an MPAA rating, so they went out with it anyway, unrated. They couldn’t advertize. And the audience at the time didn’t want that kind of film. The core audience of the film was pissed off, because what they wanted to see was more of the same. But as with a lot of my pictures I made something that was actually appreciated ten or fifteen years later. It has a lot of fans now. Looking back, it’s one of those strange films, where you wonder how it ever got made. You don’t know why it exists, like SHOWGIRLS, which I liked a lot. Taking chances is cool, but it may not be smart. Those were cool times. Life was cool. What can I say?

Dueling chainsaws: Leatherface and Dennis Hopper square off in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2

After that there was a four year gap, after which you made SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTION, which was a more modest picture in size and budget.

Was it four years? I remember that I really became involved with living in the Beverly Hills house, with the pool and all of that. My interests shifted to buying art deco and art nouveau and sitting back and watching, becoming part of the audience again. There were years that, looking back, seemed like months. Maybe I was doing what Kubrick would do. He took some really long periods between movies. He was really a cool guy too. He bought his own 35 mm print of CHAIN SAW and I got to know him a little bit.

Did you lose some of your enthusiasm for filmmaking by doing those bigger movies?

Well, it all depended on what was offered to me. I’m ashamed to say that I turned down some films that would have changed my entire life.

Any titles you can name?

I’m too embarrassed to say. It still blows my mind. I’ll never be able to forget it, although I am trying. There were a lot of mistakes.

After THE MANGLER I read this script for a television pilot and I thought: this is really cool! It was a feature length pilot that I did not think would have much chance of getting picked up. It was just too messed up. Then I got a call to get back to LA immediately, because they wanted to start prepping. So I went back, I shot the thing and it got picked up. Then I got an offer to do another pilot and that got picked up. And a third one got picked up. Then I got an overall deal with Disney to develop and do TV series. In some ways that gave me more freedom. That lasted for about five years, it seems like.

Are you still working on projects?

Yes, there’s two at the moment. One is a genre picture, the other is outside of the genre. I worry that if I do something outside the genre… How will it be perceived? I’m so clogged into the genre…

I’m going through a process that is much like a dog who’s coming out of the water and shaking the water off. I’m reorienting. To give you an example of where I would like to have gone, is to make a transition the way Polanski did. I would have liked to end up doing something like CHINATOWN.

Is it still possible?

Yeah, I think so. I’ve learned a lot and my interests are different these days. I would like to say they’re more sophisticated.

When you started out in the early seventies, making movies was still very mysterious to many people. But nowadays everybody knows so much about the process. Has it lost some of the magic?

You mean to me or the general audience?

I mean the audience.

I think it has, since everyone with an iPhone can make a movie. I think it’s really great, but it is going to alter cinema as we know it. Maybe that’s a good thing. What really surprises me about the easy access to digital filmmaking nowadays, is that there’s still only a very small group of really good filmmakers. Back in the seventies you had a small group, which I was a part of. And now there’s also just a really small group of people that are breaking boundaries and taking us to the next level.

Who do you consider part of that small group now?

Paul Thomas Anderson. Fabrice Du Welz. Just to name one American and one European filmmaker.

Did you ever go back to Austin or do you still live in LA?

I tried to move back to Austin, but I had become so accustomed to the smog in LA … The air was just too clean in Austin. And it took so long for me to get to LA if I had to be there. It was really strange: I was about ten years old when I knew I wanted to move to LA. Breaking free again from Austin took a while. I would buy a house and sell it. That happened three times. Finally, I left again and went back to LA. But now I would rather live in Europe.

I never really left LA though. I always kept a place there. It did become my home, even though it is just as dysfunctional as my childhood in Texas. Although I don’t really like LA, there is something about it. The ghosts of things that could have been.

Tobe Hooper on the set of Lifeforce

Related talks

This interview first appeared in a shorter version in the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws. Above is the full version of this talk, edited only for clarity